Spondylolysis and Spondylolisthesis

Spondylolysis is a crack or stress fracture in one of the vertebrae, the small bones that make up the spinal column. The injury most often occurs in children and adolescents who participate in sports that involve repeated stress on the lower back, such as gymnastics, football, and weight lifting.

In some cases, the stress fracture weakens the bone so much that it is unable to maintain its proper position in the spine—and the vertebra starts to shift or slip out of place. This condition is called spondylolisthesis.

Spondylolysis and Spondylolisthesis

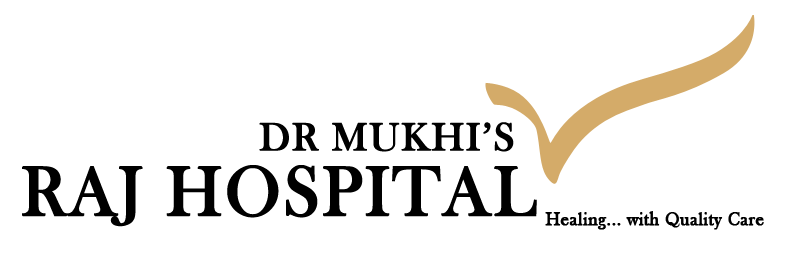

Anatomy

Your spine is made up of 24 small rectangular-shaped bones, called vertebrae, which are stacked on top of one another. These bones connect to create a canal that protects the spinal cord.

The five vertebrae in the lower back comprise the lumbar spine.

Other parts of your spine include:

Spinal cord and nerves. These “electrical cables” travel through the spinal canal carrying messages between your brain and muscles. Nerve roots branch out from the spinal cord through openings in the vertebrae.

Facet joints. Between the back of the vertebrae are small joints that provide stability and help to control the movement of the spine. The facet joints work like hinges and run in pairs down the length of the spine on each side.

Intervertebral disks. In between the vertebrae are flexible intervertebral disks. These disks are flat and round and about a half inch thick. Intervertebral disks cushion the vertebrae and act as shock absorbers when you walk or run.

Description

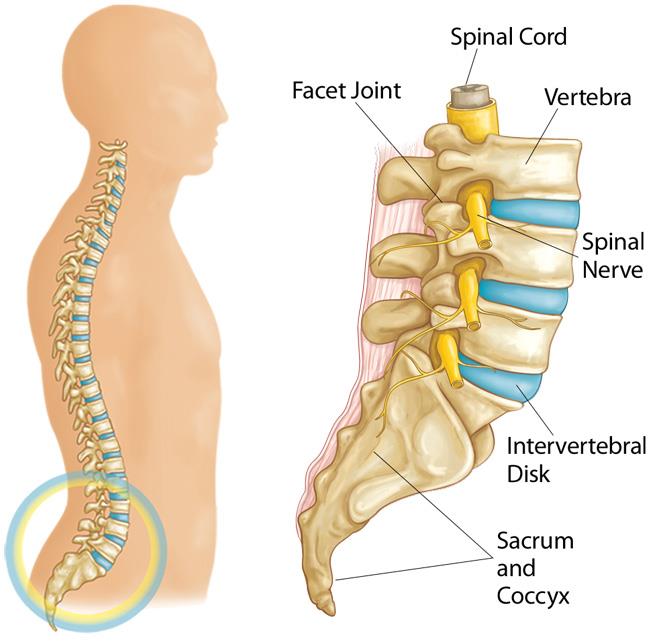

Spondylolysis and spondylolisthesis are different spinal conditions—but they are often related to each other.

Spondylolysis

In spondylolysis, a crack or stress fracture develops through the pars interarticularis, which is a small, thin portion of the vertebra that connects the upper and lower facet joints.

Most commonly, this fracture occurs in the fifth vertebra of the lumbar (lower) spine, although it sometimes occurs in the fourth lumbar vertebra. Fracture can occur on one side or both sides of the bone.

The pars interarticularis is the weakest portion of the vertebra. For this reason, it is the area most vulnerable to injury from the repetitive stress and overuse that characterize many sports.

Spondylolysis can occur in people of all ages but, because their spines are still developing, children and adolescents are most susceptible.

Many times, patients with spondylolysis will also have some degree of spondylolisthesis.

Spondylolisthesis

If left untreated, spondylolysis can weaken the vertebra so much that it is unable to maintain its proper position in the spine. This condition is called spondylolisthesis.

In spondylolisthesis, the fractured pars interarticularis separates, allowing the injured vertebra to shift or slip forward on the vertebra directly below it. In children and adolescents, this slippage most often occurs during periods of rapid growth—such as an adolescent growth spurt.

Doctors commonly describe spondylolisthesis as either low grade or high grade, depending upon the amount of slippage. A high-grade slip occurs when more than 50 percent of the width of the fractured vertebra slips forward on the vertebra below it. Patients with high-grade slips are more likely to experience significant pain and nerve injury and to need surgery to relieve their symptoms.

Cause

Overuse

Both spondylolysis and spondylolisthesis are more likely to occur in young people who participate in sports that require frequent overstretching (hyperextension) of the lumbar spine—such as gymnastics, football, and weight lifting. Over time, this type of overuse can weaken the pars interarticularis, leading to fracture and/or slippage of a vertebra.

Genetics

Doctors believe that some people may be born with vertebral bone that is thinner than normal—and this may make them more vulnerable to fractures.

Symptoms

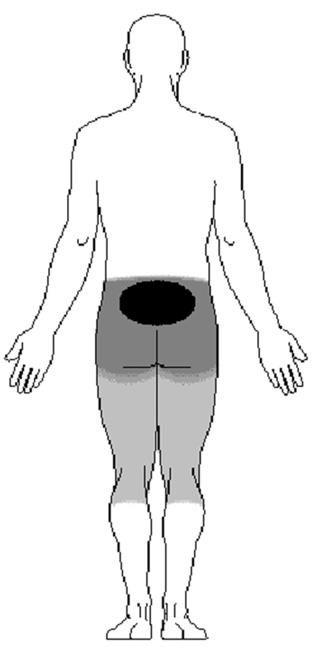

In many cases, patients with spondylolysis and spondylolisthesis do not have any obvious symptoms. The conditions may not even be discovered until an x-ray is taken for an unrelated injury or condition.

When symptoms do occur, the most common symptom is lower back pain. This pain may:

- Feel similar to a muscle strain

- Radiate to the buttocks and back of the thighs

- Worsen with activity and improve with rest

In patients with spondylolisthesis, muscle spasms may lead to additional signs and symptoms, including:

- Back stiffness

- Tight hamstrings (the muscles in the back of the thigh)

- Difficulty standing and walking

Spondylolisthesis patients who have severe or high-grade slips may have tingling, numbness, or weakness in one or both legs. These symptoms result from pressure on the spinal nerve root as it exits the spinal canal near the fracture.

Doctor Examination

Physical Examination

Your doctor will begin by taking a medical history and asking about your child’s general health and symptoms. He or she will want to know if your child participates in sports. Children who participate in sports that place excessive stress on the lower back are more likely to have a diagnosis of spondylolysis or spondylolisthesis.

Your doctor will carefully examine your child’s back and spine, looking for:

- Areas of tenderness

- Limited range of motion

- Muscle spasms

- Muscle weakness

Your doctor will also observe your child’s posture and gait (the way he or she walks). In some cases, tight hamstrings may cause a patient to stand awkwardly or walk with a stiff-legged gait.

Imaging tests will help confirm the diagnosis of spondylolysis or spondylolisthesis.

Imaging Tests

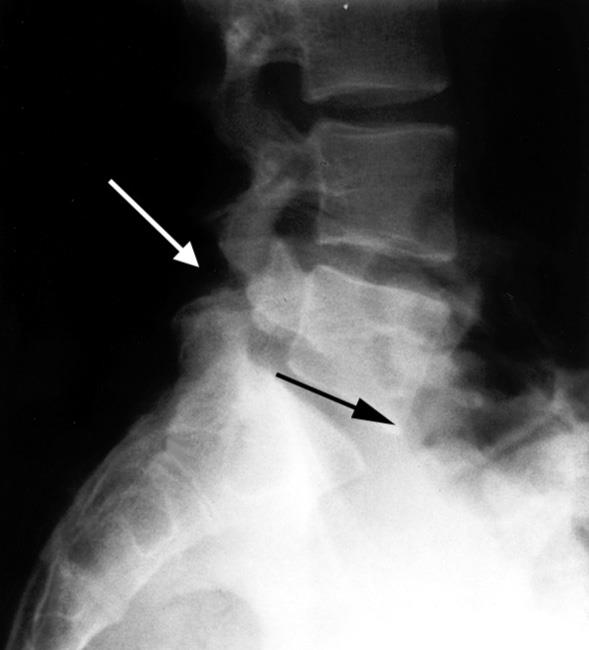

X-rays. These studies provide images of dense structures, such as bone. Your doctor may order x-rays of your child’s lower back from a number of different angles to look for a stress fracture and to view the alignment of the vertebrae.

If x-rays show a “crack” or stress fracture in the pars interarticularis portion of the fourth or fifth lumbar vertebra, it is an indication of spondylolysis.

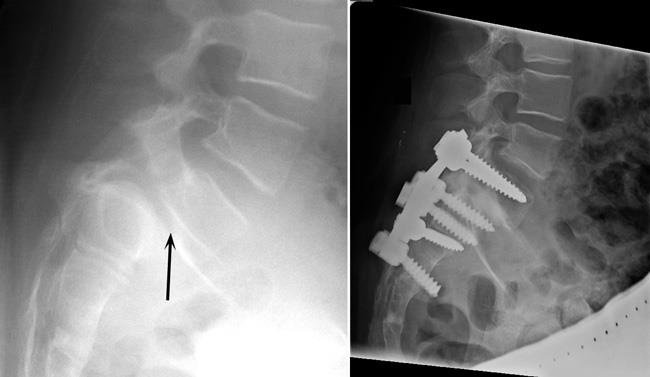

If the fracture gap at the pars interarticularis has widened and the vertebra has shifted forward, it is an indication of spondylolisthesis. An x-ray taken from the side will help your doctor determine the amount of forward slippage.

Computerized tomography (CT) scans. More detailed than plain x-rays, CT scans can help your doctor learn more about the fracture or slippage and can be helpful in planning treatment.

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scans. These studies provide better images of the body’s soft tissues. An MRI can help your doctor determine if there is damage to the intervertebral disks between the vertebrae or if a slipped vertebra is pressing on spinal nerve roots. It can also help your doctor determine if there is injury to the pars before it can be seen on x-ray.

Treatment

The goals of treatment for spondylolysis and spondylolisthesis are to:

- Reduce pain

- Allow a recent pars fracture to heal

- Return the patient to sports and other daily activities

Nonsurgical Treatment

Initial treatment is almost always nonsurgical in nature. Most patients with spondylolysis and low-grade spondylolisthesis will improve with nonsurgical treatment.

Nonsurgical treatment may include:

Rest. Avoiding sports and other activities that place excessive stress on the lower back for a period of time can often help improve back pain and other symptoms.

Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs). NSAIDs such as ibuprofen and naproxen can help reduce swelling and relieve back pain.

Physical therapy. Specific exercises can help improve flexibility, stretch tight hamstring muscles, and strengthen muscles in the back and abdomen.

Bracing. Some patients may need to wear a back brace for a period of time to limit movement in the spine and provide an opportunity for a recent pars fracture to heal.

Over the course of treatment, your doctor will take periodic x-rays to determine whether the vertebra is changing position.

Surgical Treatment

Surgery may be recommended for spondylolisthesis patients who have:

- Severe or high-grade slippage

- Slippage that is progressively worsening

- Back pain that has not improved after a period of nonsurgical treatment

Spinal fusion between the fifth lumbar vertebra and the sacrum is the surgical procedure most often used to treat patients with spondylolisthesis.

The goals of spinal fusion are to:

- Prevent further progression of the slip

- Stabilize the spine

- Alleviate significant back pain

Surgical Procedure

Spinal fusion is essentially a “welding” process. The basic idea is to fuse together the affected vertebrae so that they heal into a single, solid bone. Fusion eliminates motion between the damaged vertebrae and takes away some spinal flexibility. The theory is that, if the painful spine segment does not move, it should not hurt.

During the procedure, the doctor will first realign the vertebrae in the lumbar spine. Small pieces of bone—called bone graft—are then placed into the spaces between the vertebrae to be fused. Over time, the bones grow together—similar to how a broken bone heals.

Prior to placing the bone graft, your doctor may use metal screws and rods to further stabilize the spine and improve the chances of successful fusion.

In some cases, patients with high-grade slippage will also have compression of the spinal nerve roots. If this is the case, your doctor may first perform a procedure to open up the spinal canal and relieve pressure on the nerves before performing the spinal fusion.

Outcomes

The majority of patients with spondylolysis and spondylolisthesis are free from pain and other symptoms after treatment. In most cases, sports and other activities can be resumed gradually with few complications or recurrences.

To help prevent future injury, your doctor may recommend that your child do specific exercises to stretch and strengthen the back and abdominal muscles. In addition, regular check-ups are needed to ensure that problems do not develop.